When confronted with the idea of the federal government creating a “Muslim registry,” an ally of president-Elect Trump cited the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War 2 as a precedent. But a full year before the attacks on Pearl Harbor, American officials were compiling registries of foreign nationals, including those living in Maine. The Maine alien registry, created on the order of Governor Lewis Barrows, recorded the names of all adult non-citizens registered in the state in June1940. While the United States was still officially neutral in the wars against Germany and Japan, the Roosevelt administration had begun supplying the United Kingdom with ships and other materiel. As a border state, Maine was also at risk from espionage activities. During World War I, German saboteurs had destroyed the international bridge at Vanceboro, so there was some reason for Maine’s officials to be jittery.

The Maine State Library recently published the alien registry in its entirety online, including 35,000 individual registration forms and data sheets offering statistical information. These documents provide a new resource for genealogists, as well as historians of immigration in Maine. They also help us understand the process and consequences of creating such a registry.

Ecole St. Pierre, Lewiston, Maine, 1910. Image: USM Franco-American Collection / Maine Memory Network

Of the 35,000 foreign nationals registered in Maine, the vast majority were Canadians (who were then still technically British subjects). New Brunswickers actually comprised the bulk of these, followed by Québécois(es). These 35,000 adults represented 4% of the state’s population in 1940. Today, there are 19,000 total non-citizens in Maine, of a population of 1.3 million (1.5%). The origins of the earlier generation of immigrants is also different. Aside from the Canadians, nearly all the other immigrants were of European birth, with only a handful of Chinese, Japanese and Middle-Eastern immigrants in the state in 1940.

Among those who submitted registrations, there’s a huge degree of variation, from recent immigrants like Rev. François Drouin, pastor of Sts Peter and Paul in Lewiston, to people like Miss. Arzélie Janelle, who had been living in Maine for more than sixty years, without naturalizing (this phenomenon was most common among women, who could not vote until, and for whom citizenship therefore held less value). Together with her sisters, Victoria and Marie-Anne, Arzélie ran a well-known clothing store on Lewiston’s Lisbon Street. By contrast, some of the registrants, like Albertine Michaud, of Sanford were unable to read or write. While those on the register were asked which language they spoke, there is no statistical data on the number of Francophones among the Canadians. There are, however, plenty of examples of individuals who did not speak any English, or who could speak, but not read it.

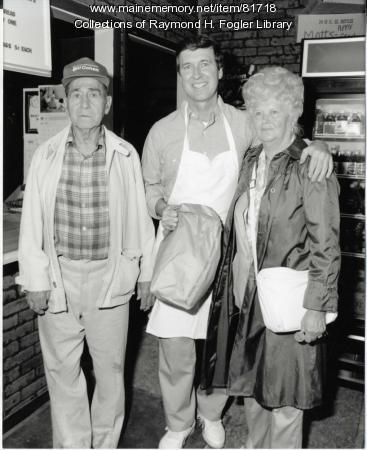

Bill Cohen (center) with parents Reuben and Clara, Rye Bread Bakery, Bangor, Maine, 1984. Reuben was employed as a baker in 1940. Image: University of Maine, Raymond H Folger Library / Maine Memory Network

There are also a number of prominent Mainers, or their ancestors, on the registry, including the parents of future US senators Bill Cohen and George Mitchel, and the grandfather of Sen. Olympia Snowe . These examples are reminders that many of Maine’s most prominent citizens descended from humble immigrant families.

One sinister aspect of the registry is that its presence encouraged a Mainers to inform the authorities of suspicious individuals. One anonymous informant was concerned about activities at “Larry Burch’s Log Cabin on Route 202”; “A foreign-looking man” who took photographs of the Bangor Water Works was cause for concern for one Maine citizen. Oliver Hamlin, a great-grandson of US Vice-President Hannibal Hamlin, wrote extensively about several persons of interest to the Adjutant General’s office, which oversaw the registry.

After the registry had been created, officials created a series of index cards for a small number of individuals, presumably those deemed of special interest. These were largely German and Russian speakers and suspected communists (in addition to the ongoing red scare, the USSR and Nazi Germany were not yet at war, and had collaborated in the invasion of Poland in 1939). In an ironic and tragic twist, most of these Russian and German nationals appear to have been Jewish (by their surnames). The very same group of people who had had fled persecution in Europe were being singled out for their nationality in their new homeland.

In the end, that may be the lesson to draw from Maine’s alien registry. There are no documents to show that the records drawn up were ever used to prosecute individuals, and in the process of singling out tens of thousands of residents who happened to be foreign nationals, the state undermined some of the very freedoms the US would soon go to war to protect.